In the late 1940’s, the US Air Force had a serious problem. Its pilots kept crashing planes. At its worst point, 17 pilots crashed in a single day. At first, pilot error was seen as the primary cause. There were no mechanical or electronic issues in the vast majority of planes that crashed. All of the data seemed to show there was something wrong with the pilots. However, the pilots also were well trained, and were able to demonstrate in various test runs that their skills were not the problem. So if it wasn’t mechanical error, and it wasn’t human error, what was the problem?

They investigated just about everything and still couldn’t find the cause. Finally, the only thing left to look at was the design of the cockpit. The first American cockpit had been designed in 1926. Engineers had measured the physical dimensions of hundreds of pilots and used that data to create the standard dimensions of a cockpit. For roughly the next 30 years, the size and shape of the seat, distance to the pedals and stick, height of the windshield and even the shape of the helmets were built to conform to these measurements taken in 1926.

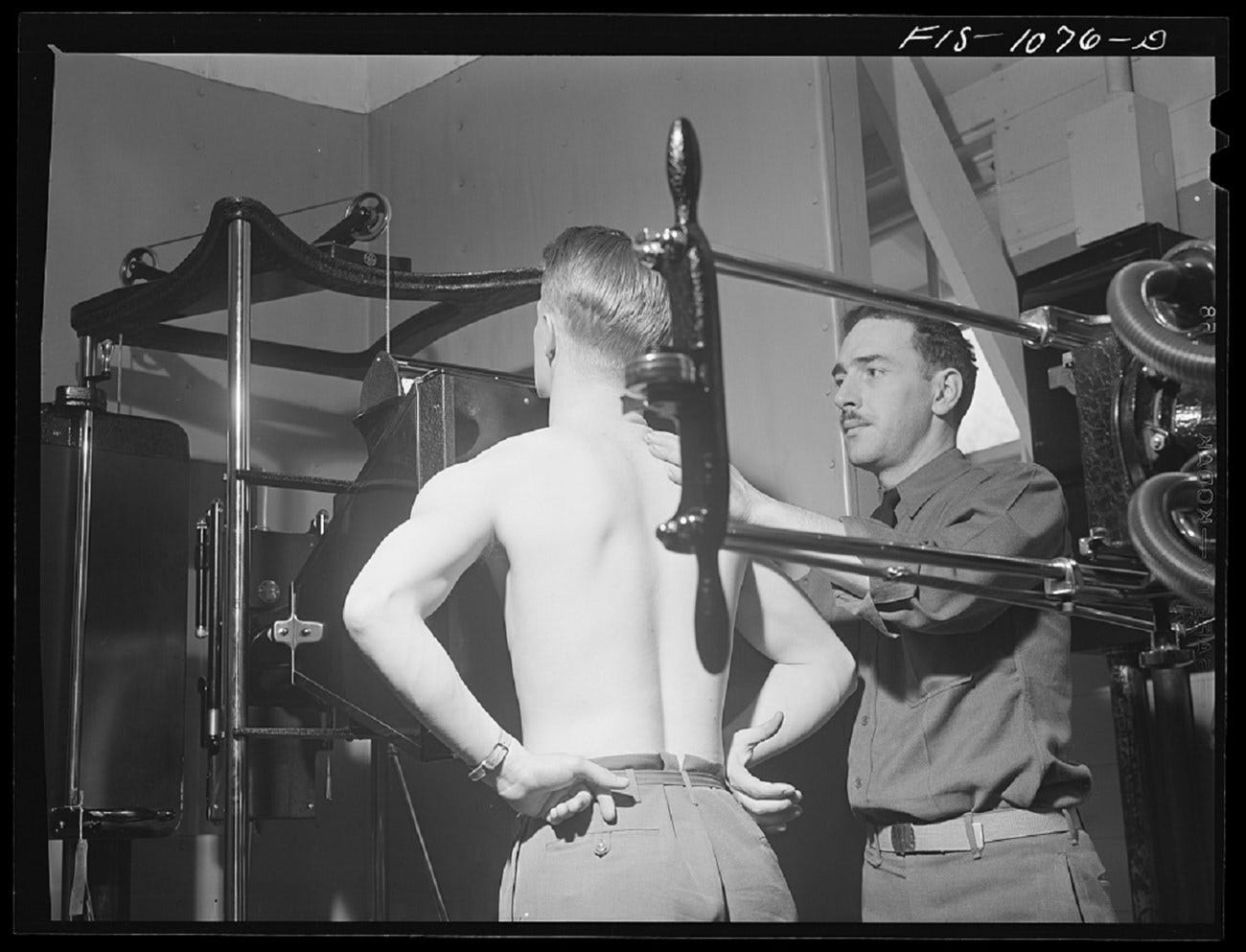

Engineers started to think that pilots had gotten bigger since 1926. The Air Force authorized the largest study of pilots ever undertaken. In 1950, researchers at Wright Air Force Base in Ohio measured more than 4,000 pilots on 140 dimensions of size, including thumb length, crotch height, and the distance from a pilot’s eye to his ear, and then calculated the average for each of these dimensions. Everyone believed this improved calculation of the average pilot would lead to a better-fitting cockpit and reduce the number of crashes — or almost everyone.

Lt. Gilbert Daniels was a 23 year old junior researcher whose job it was to measure pilot’s limbs with a tape measure. Daniels had gone to Harvard, and in his undergrad thesis, he had actually created a comparison of 250 male hands. Even though they were all white, and from similar socio-economic backgrounds, their hands were not similar at all. And when he averaged the data, the average hand did not resemble any individual’s measurements. Daniels realized early in his career that there was no such thing as an “average individual.”

Now, in the Air Force, he took the data that had been gathered from 4,063 pilots and calculated the average 10 dimensions he believed were most relevant for cockpit design. These formed his dimensions of an “average pilot.” He reasoned that if an individual’s measurements were within 30% of this average, they would fit in the cockpit just fine. For instance, the “average pilot” was 5’9. So a pilot would have to be between 5’7 and 5’11 to fit in the cockpit. Then, he took these 10 average measurements and compared each individual pilot, one by one to the “average pilot.” His fellow researchers saw this as a waste of time. They thought they knew with complete certainty that the vast majority of pilots would fit into the average range on these 10 dimensions. After all, they had manually selected these pilots specifically because they appeared to be average size. For instance, a person who was 6’7” would never have been recruited to be a pilot.

When Daniels did his comparisons, out of 4063 pilots measured. Not a single one fit within the average range. One pilot might have a longer-than-average arm length, but a shorter-than-average leg length. Another pilot might have a big chest but small hips. Daniels discovered that if you narrowed it down to just three of the ten dimensions of size — say, neck circumference, thigh circumference and wrist circumference — less than 3.5% of pilots would be average size. There was no such thing as an average pilot. If you’ve designed a cockpit to fit the average pilot, you’ve actually designed it to fit no one.

The Air Force immediately changed its design philosophy. The guiding principle of designing cockpits became the principle of “individual fit.” Rather than fitting the individual to the system, they fit the system to the individual. They designed adjustable seats and adjustable foot pedals as well as adjustable helmet straps and flight suits. Once these, and other design solutions were put into place, pilot performance soared, and the U.S. Air Force became the most dominant air force on the planet. Soon, every branch of the American military published guides decreeing that equipment should fit a wide range of body sizes, instead of standardized around the average. This design philosophy also eventually made its way to consumers. Car manufacters added adjustable seating and steering wheels. And as car seat manufacturers realized the same thing was true for children. They created adjustable car seats.

Daniels summed up the findings this way:

“The tendency to think in terms of the ‘average man’ is a pitfall into which many persons blunder … It is virtually impossible to find an average airman not because of any unique traits in this group but because of the great variability of bodily dimensions which is characteristic of all men.”

Here’s what I find fascinating: most of us, in some way, feel pressure to conform to average. But none of us will ever fit average.

normal is a myth

There’s this pressure to fit into “normal” but normal isn’t even a thing that exists. To be normal is to “conform to a standard.” But when we look at the standard, even if we try to fit it, it will not fit any of us. “Average” is a standard created for everyone that ends up fitting no one.

In ancient Greece, ἄτοπος described something or someone as strange, absurd, or out of the ordinary. Topos means “place,” a- means “without.” A person or thing who was atopos was “placeless” or “off the map.” In other words, an atopos person is one who cannot be neatly placed into any familiar social or intellectual location. In the ancient world, to call someone atopos was to label them “outrageous, strange, extravagant, absurd, unclassifiable, [and] disturbing”

In the writing of Plato, Socrates was frequently referred to this way.

Symposium: At Agathon’s banquet, Socrates mysteriously pauses outside in a trance instead of joining the dinner. Agathon exclaims “How strange!” at Socrates’ behavior . Later, Alcibiades praises Socrates but calls him atopos, “a most peculiar man,” because Socrates is unlike anyone else – immune to flattery, indifferent to wealth or beauty, and possessing a baffling charisma.

Gorgias: Frustrated by Socrates’ relentless logic, Callicles bursts out, “How strange (ἄτοπος) you are, Socrates!” Socrates’ perspective in this dialogue (such as claiming it is better to suffer wrong than do wrong) are seen as alien to the “average” Greek.

Socrates confounded people’s expectations at every turn. He was not considered a wise man or a statesman, neither ignorant nor conventionally wise – truly atopos, situated in no familiar category. This reputation for strangeness is one reason many Athenians viewed him with a mix of admiration and suspicion. He was not considered atopos just because he was quirky - although he was. Socrates did not seek to fit into society, but it was also not his intention to stand out. He sought to look at society’s values with fresh eyes and encourage others to do the same. His oddity was a strategy as much as a personality trait: it enabled the Socratic method of relentless inquiry. Little wonder that Alcibiades, in praising Socrates, highlighted his atopia as the quality that set him apart from all other men.

Singularity, not authenticity

Socrates was incomparable and unique, which is not the same as being different or authentic.

Byung-Chul Han explains the difference: “singularity is something totally different from authenticity. Authenticity presupposes comparability. Who is authentic is different from the others.” A singular, atopos person has no comparison; “not only is he different from the others, but is different from everything that is different from the others.”

There is so much discussion on authenticity. However, the pursuit of authenticity seems to foster more conformity than individuality. Discussions about authenticity seem to always have a sense of comparison with other people. A person who is seen as authentic is seen as authentic in contrast to all the people who aren’t authentic. In striving for authenticity, we are still comparing ourselves to the average. In trying to be “different” we actually end up becoming the same. Although we “aren’t average” we are still using average as our standard of measurement.

Is comparing our authenticity to the average persons lack of authenticity helpful to us? When we do this, we seem to inadvertently reinforce the idea of normal. We are “not normal” so we don’t check the boxes. But then we also say which box we actually belong in. We’re not really out of the box, we’re just in a different box. Authenticity is the new “average.” Like the Air Force redesigning the 1926 cockpit in 1950 thinking they just needed to create a new average.

Authenticity implies comparison. It gets out of the box to get into another box.

Yes, it is original, but also, an original in comparison to all the copies.

Singularity defies comparison. It doesn’t believe the box ever existed.

Something that is singular is beyond comparison. It is 1:1. Atopos. There is no place to put something that is singular. It doesn’t create a new category. It defies categorization.

I think we’re all supposed to be atopos.

Incomparable. Not just different from others, but fully unique. Not just “different from the others…different from everything that is different from the others”

In these definitions look at the words. To have a unique fingerprint is to seek to be singular, not just authentic. Authentic may be a way we present our singularity to the world. But maybe authenticity shouldn’t be our goal.

You’re 1:1. I’m 1:1.

You don’t fit into average. That doesn’t mean you don’t fit within a tribe. It does mean that you won’t quite fit perfectly into the average. But, you’re also not supposed to.

Be singular. To be singular means to have an understanding that you’re not meant to be in a box. You’re supposed to affect change on everything you are a part of. Like a pilot getting into the cockpit, you change the measurements of everything you’re a part of. But that’s what can, and will make you successful.

“There is nothing noble in being superior to your fellow man; true nobility is being superior to your former self.” / Ernest Hemingway

Nikola Tesla

Unlike Thomas Edison, who was a businessman as much as an inventor, Tesla lived in a different space—more interested in the beauty of his discoveries than in their profitability. He envisioned wireless electricity and technological marvels far beyond his time.

A famous anecdote shows his eccentricity: Tesla reportedly could visualize entire machines in his mind before ever building them, running complex physics calculations mentally. He shunned conventional wealth and often fed pigeons instead of pursuing financial stability. Many of his contemporaries, including Edison and J.P. Morgan, could not categorize him—was he a genius? A madman? A mystic? Tesla’s ability to exist outside both business-minded inventors and purely academic scientists made him unplaceable.

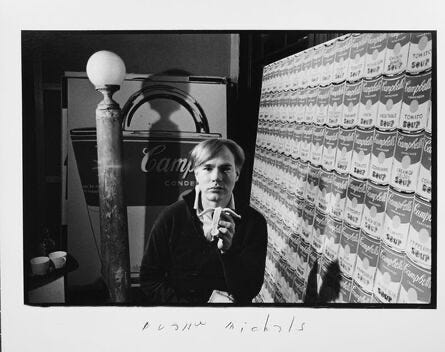

Andy Warhol

Warhol disrupted the art world by refusing to conform to the traditional ideas of artistic authenticity. His Campbell’s Soup Cans and Marilyn Monroe prints were neither entirely commercial nor entirely “high art.”

When asked what his paintings meant, Warhol would respond with non-answers: “I just paint things I like.” His deadpan personality, monotone voice, and refusal to be pinned down frustrated critics and intellectuals who wanted to categorize him as either a genius or a fraud.

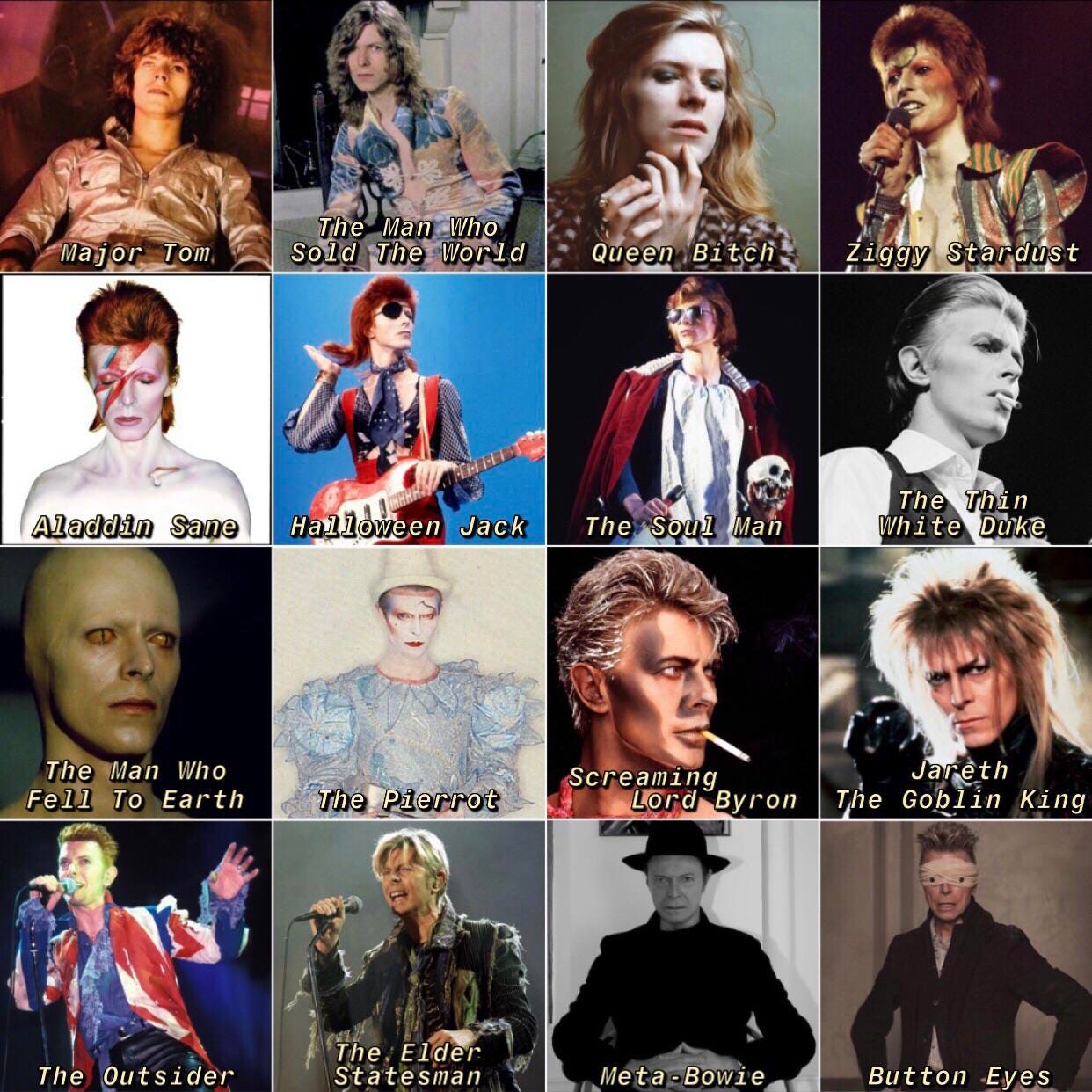

David Bowie

Bowie was never just a musician—he was an atopos cultural force. Constantly reinventing himself (from Ziggy Stardust to the Thin White Duke), he refused to settle into any stable identity. When asked in an interview how he defined himself, Bowie replied, “I don’t. I just do.” His fluid, unpredictable persona kept audiences both fascinated and slightly off-balance.

Steve Jobs

Jobs was infamous for being impossible to categorize. He wasn’t a traditional engineer like his partner Steve Wozniak, nor was he a conventional businessman like Bill Gates. He operated in a strange in-between space, thinking in terms of aesthetics, intuition, and vision rather than technicalities or profits.

A famous example: At Apple’s first major product unveiling, Jobs pulled out the iPod and simply said, “1,000 songs in your pocket.” While tech executives focused on specs and storage, Jobs focused on the experience. He thought differently—so differently that he often clashed with others who couldn’t place him into a box.